Harvesting Spell Components

Many GMs eventually find themselves facing the situation of an enterprising player character that wants to use the corpse of the creature they have just defeated as a source of spell components. Such components may be destined for the party’s own use, or might represent additional spoils of victory to be resold to the local Wizard’s guild. In the former case, the creature in question might be one that is already listed in a published spell description, or the character may just be looking for alternate components or components for a spell of their own devising.

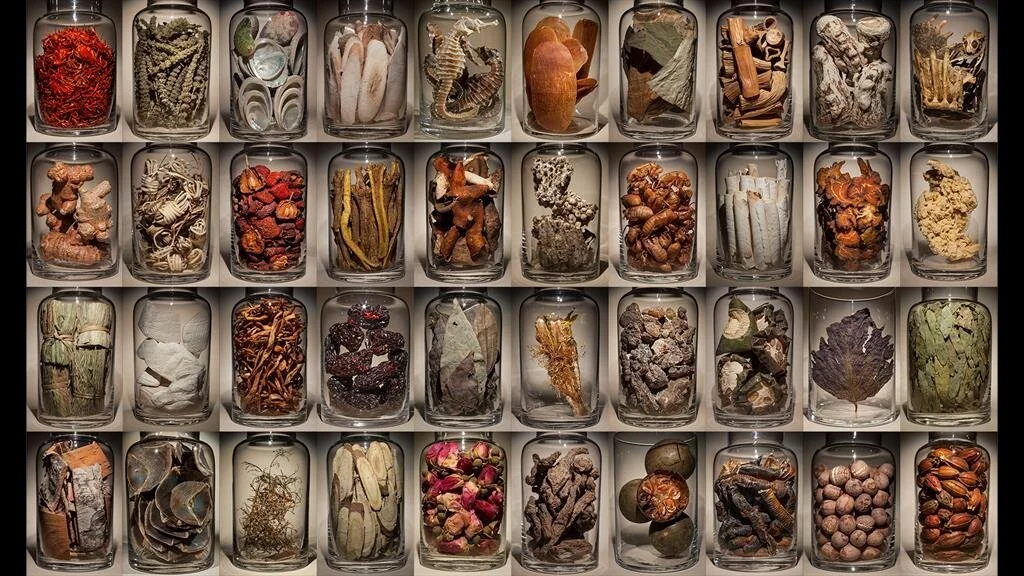

In any event, it is fair to assume that the creation of inks, potions, and diverse magic items requires innumerable esoteric components, a great number of which might be derived from various monsters. The system detailed here is meant to be a quick solution to judging whether the party can successfully remove any possible components, and how valuable those components might be to the right buyer.

The first determination is a judgment call from the GM as to whether the creature in question even possesses any magical value. Given the broad and flexible nature of the d20 magic system, however, most—if not all—creatures should be able to provide some value, based upon the traits that they possess. Special attacks, defenses, or innate magical powers would be strong indicators of possible component potential. There is also the possibility that the creature is endowed with special significance or qualities by certain cultures, which might give it some value when seeking to evoke those qualities (e.g., a lion being associated with courage or leadership ability).

Once the GM has agreed that the creature might provide some value (even if the specific nature of that value is not explicitly identified), the next step is to see if the party can ascertain which of its parts are potentially useful.

A character can determine this by making a Spellcraft or Knowledge: Arcana check, with a base DC of 15, +1 per HD of the creature (+5 if it is unique). Familiarity with a monster is also a factor, and if a character has encountered the same sort of creature before, he receives a bonus of up to +1 per previous encounter, to a maximum of +5, to the skill check. Conversely, if the party did not get to see the creature in action (e.g., simply found its corpse), or managed to defeat it before it could display its unusual properties (e.g., killing a Dragonne before it can roar), then the GM should assign appropriate penalties (e.g., –2 for each of the previously mentioned factors). If the creature is specifically listed as a component in a spell that the character knows, then success is automatic.

Success indicates that the character is able to determine what parts of the creature could be used as spell components. (If desired, GMs can identify what these parts are, but this distinction is purely cosmetic; the total usefulness or net value of a creature’s parts remains the same.) Once this has been accomplished, the next step is to harvest them.

Successful use of an applicable skill, with a base DC of 15, means that a character has managed to excise the required organs, appendages, or other body parts and prepare them for storage or travel. Appropriate skills include Survival and certain sorts of Craft or Profession skill (e.g., Craft (Taxidermy), Profession (Butcher)). Five or more ranks in an appropriate area of Knowledge can grant a +2 bonus to this skill check (e.g., Knowledge (Nature) for retrieving components from a normal animal). Note that the character that harvests the components does not need to be the same one that initially identified them. (What Wizard ever said Rangers don’t have their uses?)

Attempts to harvest spell components can be hampered or even negated by various circumstances, most commonly significant damage from combat or destructive spells. A good rule of thumb is generally a –1 modifier to the harvesting check for each die of damage or wound sustained. And note that components cannot be harvested at all from undead creatures that have been destroyed as the result of Clerical turning.

Finally, assuming a party successfully harvests a monster’s useful components and intends to sell them, the GM must determine their market value (which players can subsequently extrapolate from using an Appraise skill check with a DC equal to 10 plus the CR of the creature in question).

In general, the value of all the usable spell components that can be harvested from most creatures is equal to a number of gold pieces equal to their Challenge Rating (CR) squared (or silver pieces for CRs less than 1). These creatures include Animals, Constructs, Elementals, Giants, Humanoids, Monstrous Humanoids, Oozes, Plants, and Vermin.

Some creatures, particularly those that are especially rare or exotic, have parts that are potentially more valuable to spellcasters, and the total value of all the spell components that can be harvested from them is generally equal to their CR cubed (in gp or sp, as appropriate). They include Aberrations, Dragons, Fey, Magical Beasts, Outsiders, and Undead.

Thus, for example, the relevant parts from a Hill Giant (CR 7) would be worth 49 gp (7 gp x 7 gp = 49 gp), the proboscis of a Stirge (CR ½), a Magical Beast, would go for 125 sp (5 sp x 5 sp x 5 sp = 125 sp), and the saliva and antennae from a Rust Monster (CR 3) would go for 9 gp (3 gp x 3 gp = 9 gp). Note that in general only the base CR of a creature should be taken into consideration, and not any additional character levels it might have (unless, for example, a spellcaster was working on a dwoemer that called for the relevant parts of an Aristocrat or somesuch …).

The assumption underlying these formulas is that the more dangerous the creature, the more valuable the components (in part, at least, because so many would-be entrepreneurs wind up as lunch). This system is only intended as a consistent method for generating the value of spell components harvested from creatures, however, and the GM can adjust prices as needed to reflect specific supply and demand conditions in the market. A Game Master might rule, for example, that some items have no value at all because of their ready availability, or can be sold only in limited quantities (e.g., a party might be able to sell four units of Orc essence, but not all 40 they were hoping to unload). And trade in certain components might actually be illegal in some cultures (e.g., trade in human parts is generally prohibited in our own society).

In any case, the value of the spell components that can be derived from a particular creature are in addition to any mundane value it might have (e.g., a lion’s mane, liver, and other components might be worth a total of 9 gp to a Wizard, but its pelt might still be used to fashion a cloak).